At a new reading group in London we have been lucky enough to receive some informal translations of Dolto’s work by Sally Bird. We began by slowly reading through her very thoughtful translation of an interview with Dolto in 1978 where Dolto describes something – a concept or a notion, perhaps – which she names la fête.

La fête seems to be something akin to a momentary state of being which involves joy, surprise, a being with others, but also risk. It has both a simplicity and a complexity to it and gave rise to many thoughts about our work with young children in the community both theoretically, and practically in thinking about how we design our spaces.

A first question that arose was the translator’s decision not to translate la fête but to leave it in the original French. Our French colleagues spoke about the very specific connotations of la fête in French – a term, it is worth mentioning, that does not have the same meaning as the village fête in England. In French la fête connotes joy and community, to revel, and to feast with others. And, in Dolto’s la fête there is an enjoyment which only appears through the experience of risk. Dolto describes play itself as “the enjoying of a desire that is carried through to a successful conclusion by way of some risk”. The element of risk in what Dolto describes could not be found in the translations that the group put forward for la fête including how we understand the word ‘fête’ in the English language, and it is this aspect of what she describes, the element of risk, which particularly caught my attention.

Risk

Dolto describes “the risk of freedom”; something which takes place in a liminal space between safety and danger. Thinking of the British context, her opening remark in the interview, “La fête is freedom within security”, echoes that of A.S. Neill’s mantra ‘freedom not license’. It points us towards the idea that joy, or enjoyment needs an element of risk without danger; that risk does not mean ‘anything goes’ (as Neill was often accused of) but that ‘anything goes’ within a framework. Summerhill – the ‘school with no rules’ as the British press liked to call it – has a very fundamental framework of democratic meetings. Similarly, The Maison Verte has a framework: there is a red line (introducing the idea of a limit rather than a border) and the children wear an apron when playing with water. Within this social framework there is no normative which might be found in other settings where things like ‘developmental milestones’ are monitored and regularly assessed. At the Maison Verte there is the risk of subjectivity on offer.

Practically speaking, the discourse of ‘risky play’ which is being developed in the UK also has a very useful mantra: they talk about facilitating ‘risk not hazards’. In one demonstration for example, a play worker pulls out nails from some pieces of wood for his adventure playground. These are a hazard, he says. The fire pit in the middle of the playground, that’s a risk.

The Carnivalesque

The idea of the carnivalesque came up as a possible translation for la fête which includes risk. Although, perhaps, too rowdy and infused with profanity, Mikhail Bakhtin’s ideas of the grotesque and revolution could represent what we do at the Maison Verte, and I was intrigued by this suggestion. In fact, in a more subtle way I think we do see the Maison Verte as having a revolutionary potential. The Maison Verte makes space for the experience of both community and risk, alongside each other, and it makes space for that to be a possibility for our very youngest members of society. Dolto advocates for children to have spaces where they can meet others but also take risks and Dolto described the work as ‘psychoanalysis on the street’. She saw the Maison Verte as the people’s agora which sits outside of the council driven, risk averse, bureaucratic institutions of the nursery and the crèche.

The grotesque aspect of the carnivalesque also resonates. Bakhtin describes the grotesque as a literary trope which expresses “biological and social exchange”. There is an emphasis on the holes of the body – the mouth, the anus – as that through which the outside world enters and leaves: through eating, shitting, singing, burping etc. When reminding myself of Bakhtin’s theory which I read more than 10 years ago, before any engagement with psychoanalysis, I was immediately reminded of the drive and its objects which circulate; the anal, oral, voice and gaze. While at the heart of any psychoanalysis the drive is of particular importance for young children and their parents as they learn to speak, eat solid foods, become ‘potty trained’ and become subjects with a relationship to both the body and the social bond.

Lastly, the carnivalesque, in Bakhtin’s analysis, is constructed through polyphonic dialogue which he describes as creating a ‘dialogic sense of truth’. It involves a decentralisation of the authorial voice in favour of simultaneous points of view. Applying this to our work, I am of course reminded of the Welcomers’ role and the structure which sees a rotation of those who intervene. Welcomers speak neither from the position of the expert nor from the position of the ‘institution’. At a Maison Verte one experiences a polyphony of voices including the Welcomers, other parents and, of course, the children themselves.

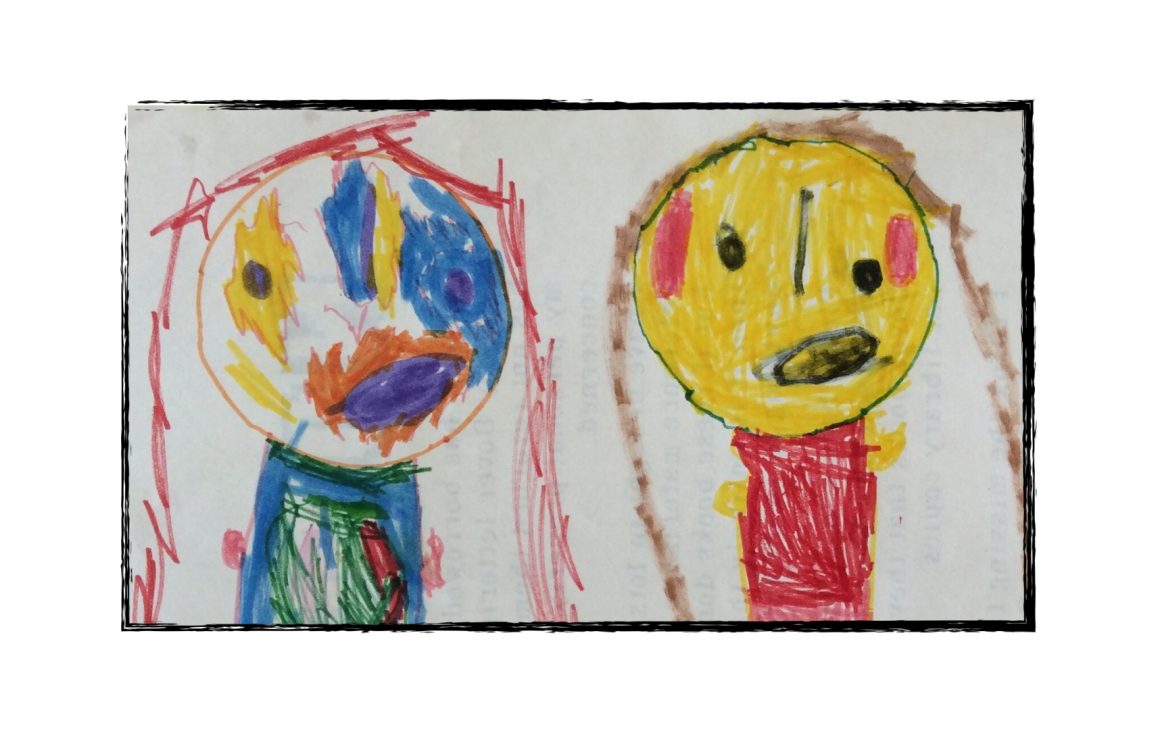

While I don’t mean to make a direct comparison between the carnivalesque and Dolto’s concept of la fête, I do think that this sometimes ungraspable phenomenon we call play is a revolutionary work when we give it space. In this interview Dolto describes play as “the enjoying of a desire that is carried through to a successful conclusion by way of some risk” and I am reminded of the video below.

Written by Catherine from The Green House Playgroup